Cider was the Island’s biggest export and the “national crop” well before the arrival of the Jersey Royal potato. The quality of both Jersey apples and cider was held in high esteem in France and the UK, but the industry eventually went into decline and only a handful of orchards remain today

Apple orchards and cider-making are an intrinsic part of Jersey history, having once shaped the landscape, culture and economy of the Island. During the early 19th century, no Jersey table was considered complete without a bottle of cider and apple orchards filled the countryside. Cider was the Island’s biggest export and the “national crop” well before the arrival of the Jersey Royal potato. The quality of both Jersey apples and cider was held in high esteem in France and the UK, but the industry eventually went into decline and only a handful of orchards remain today.

The first recorded evidence of cider in Jersey dates from the 15th century but it was probably made here long before that for local consumption. In mid-17th century Britain, when existing agriculture went into a decline, cider was seen as an alternative source of revenue. Orchards were planted and cider soon became the champagne of Britain and the national drink – the wealthy drinking vintage cider and the rest of society drinking farmhouse cider. In Jersey, the planting of orchards and cider-making grew rapidly once the potential for profit was realised and it developed into a thriving local industry. Until the First World War, cider was an integral part of day-to-day life in Jersey and commonly drunk with meals, particularly on farms.

In 1682, Jean Poingdestre wrote: “There is hardly a house in the Island, except in St Helier, that did not have an orchard of from one to two vergees, sufficient to produce an average of 20 hogsheads a year.” (One hogshead was the equivalent of 54 gallons). In his History of Jersey of 1692, Reverend Philippe Falle commented: “I do not think there is any country in the world that, in the same extent of ground, produces so much cider as Jersey does, not even Normandy itself.”

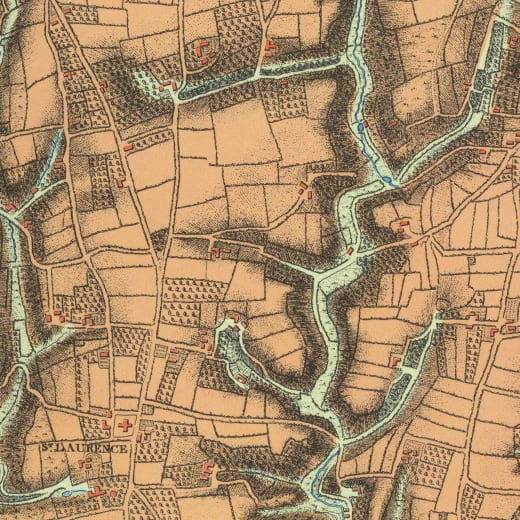

The extent of orchard planting had a dramatic effect on the rural landscape. Previously, cereal crops had been planted in large open fields. However, apple trees were planted in smaller fields enclosed by earth banks and hedges to provide shelter from the prevailing winds. Small lanes provided access to the fields and the countryside took on the familiar pattern that we know today. The proliferation of orchards across the Island is graphically illustrated by the Duke of Richmond map of 1795. Around 16% of the total land area was planted with orchards with more than a third of the parish of St Saviour being given over to apple growing.

As well as changing the appearance of the countryside, the cider industry also transformed the economy. Farms had been generally self-sufficient, growing a mix of crops and keeping a variety of animals to meet the needs of the family. Once the value of apples was recognised as a cash crop, corn growing was almost entirely replaced by apple cultivation and the Island was no longer self-sufficient in grain. So dire was the situation that in 1673, the States of Jersey outlawed new orchards because of the cost of importing grain to feed the population. Only trees that replaced existing ones could be planted.

By 1790, Reverend Francois Le Couteur, founder of the first Jersey Agricultural Society and cider expert, estimated that 30,000 to 35,000 barrels were produced annually – 20,000 for local consumption and the rest for export. In a report for London’s Board of Agriculture in 1815, Thomas Quayle described some of the local apple varieties: “The cider apple most generally favoured at present is a native species and bears the name of Romeril from a family of that name in the Island, by whom it was first grafted from the wild stock …The Noir-toit, a sweet fruit, and the Gros-Amer, rather bitter, are all Jersey apples, valued on account of their size and being good bearers. The Pain-Sauce, Rogneux and the Frechen or Frequin, a bitter-sweet apple, are also natives of Jersey, of esteemed quality but bad bearers. The Ameret-aux-Gentilshommes also answers the same description and ripens late. Each of these is still grown, but in small quantities; their fruit is mixed with the others, in order to give quality.”

Apple yields tend to fluctuate, with a good year followed by a bad one. In 1680, there were so many apples that the Island ran out of barrels for holding all the cider! By contrast, 1827 and 1831 are recorded as years of complete failure of the apple crop when even eating apples had to be imported from England. In times of plenty, the Island depended on immigrant labour to harvest the apples, most workers coming from nearby France. For a long time, these seasonal French workers were paid partly in cider and, as in England, large quantities were drunk during the working day, especially at harvest time. Stoneware jugs of cider would be filled from the barrel and carried to the fields. In the 20th century, the increasing mechanisation of agriculture made drinking at work both dangerous and illegal, but local farmers still supplied cider for the French workers, who came to pick potatoes until at least the 1940s.

Despite the high reputation of Jersey cider, by the 1860s the industry had fallen into a steep decline. Exports in the 1850s had averaged 150,000 gallons but by 1875 this was down to 3,000 gallons. Around this time, many orchards were felled to make way for growing potatoes, a crop with a more consistent yield. Exports of potatoes were growing rapidly and the development of the Jersey Royal potato in the 1880s was a very lucrative time for Jersey farmers. The Occupation years saw a slight revival in cider-making on local farms but in the postwar years, the land reverted to potato growing and a big storm in 1947 uprooted many of the remaining apple trees.

Thankfully, today there is a growing interest in cider-making and the more unusual local varieties of apples. A small orchard was planted at Hamptonne in 1991 and these apple trees now provide fruit for the annual cider-making festival. Over the weekend of the festival, visitors can admire the magnificent spectacle of tonnes of apples being crushed the traditional way, using a horse (the star of the show) to power the granite crusher. The pulp is shovelled out and transferred to the twin-screw press. It is then squeezed between sheets of hessian which are called ‘cheeses’ and the golden juice drips from the press into a huge vat. The juice is then decanted into barrels and sealed. Nothing is added to the juice – it ferments naturally over the winter and is ready for tasting at the next Cider Festival. Last year’s vintage is, of course, already available to taste!

Podcasts

Listen to our podcasts to find out the story of Jersey. Brand new series of podcasts; Small Island Big Story now available!

Find out more

The Coin Hoard comes home

The story of Le Câtillon II, the largest hoard of Iron Age gold and silver coins, jewellery and ingots ever found in Western Europe.

Find out more

Hamptonne Country Life Museum

A picturesque country farm estate from the 15th century sharing the story of Jersey’s rural life.

Find out more