Learn about the corn riots of 1769, why they happened and how public protest inspired change

A monopoly on power

During the 18th century, power in Jersey was concentrated in the hands of the Lemprière family. In 1750, Charles Lemprière was appointed Lieutenant Bailiff, while his brother Philippe was named Receiver-General.

One of Charles Lemprière’s major opponents within the Island was Nicholas Fiott. He was a captain and merchant who had disagreements with Lemprière going back many years. Things came to a head in the mid-1760s when Fiott struggled to find a lawyer to represent him in the Royal Court as they were all appointed by Lemprière. Finally, Fiott took his frustrations to the Court.

This was the opportunity for which Lemprière had been waiting. Fiott made his objections in writing and was prosecuted by Lemprière for insulting members of the Court. Fiott was fined and sentenced to ‘amende honorable’, which meant that he had to get down on his knees and pray for the forgiveness of God, the King and the Court. He refused to comply with the sentence and was sent to prison for a month. On his release, Fiott left the Island.

Charles Lemprière, Lieutenant Bailiff of Jersey

Rising food prices

In 1767, people protested about the export of grain from the Island. Anonymous threats were made against shipowners and a law was passed the following year to keep corn in Jersey. In August 1769 the States of Jersey repealed this law, claiming that crops in the Island were plentiful. There was suspicion that this was a ploy to raise the price of wheat, which would be beneficial to the rich, many of whom had ‘rentes’ owed to them on properties that were payable in wheat. As major landowners, the Lemprière family stood to profit hugely.

Acts of resistance

In the summer of 1769, a ship loaded with corn for export was raided by a group of women who demanded that the sailors unload their cargo and sell it in the Island.

Let us die on the spot, rather than by languishing in famine. God hath given us corn, and we will keep it, in spite of the Lemprières, and the court, for if we trust to them they will starve us.

The Corn Riots

On Thursday 28 September 1769, a Court called the Assize d’Héritage was sitting, hearing cases relating to property disputes. The Lieutenant Bailiff, Charles Lemprière, sat as the Head of the Court. Meanwhile, a group of disgruntled individuals from Trinity, St Martin, St John, St Lawrence and St Saviour marched towards Town where their numbers were swelled by residents of St Helier.

The group was met at the door of the Royal Court and was urged to disperse and send its demands in a more respectful manner. However, the crowd forced its way into the Court Room armed with clubs and sticks.

Inside, they ordered that their demands be written down in the Court book although the King later commanded that the lines be removed from the book.

The Court records with the demands of the protestors crossed out on the orders of the King

The aftermath

In the days following the riot there was relative peace in the Island. On Saturday the demands were published in the Public Market, and on Sunday they were proclaimed in the majority of the parishes. On Sunday evening, however, the Lieutenant Bailiff and the Jurats fled to Elizabeth Castle for safety. Perhaps there was a threat received, or they thought it would look good politically if they seemed to be in danger.

'Elizabeth Castle’ by Dominic Serres, 1764

On 6 October, a meeting of the States of Jersey was held at the Castle when it was agreed that Charles Lemprière, together with two Jurats, and Philippe Lemprière, the Attorney General, would journey to London in order to present their difficulties to the Privy Council, representing the Crown.

At first, the Privy Council was outraged by their reports and commanded that the demands of the rioters be erased from the Court records. On 1 November, a Royal Pardon and a reward of £100 was offered to any rioters who named the ringleaders.

After the full situation in the Island became clear, the protestors were eventually pardoned.

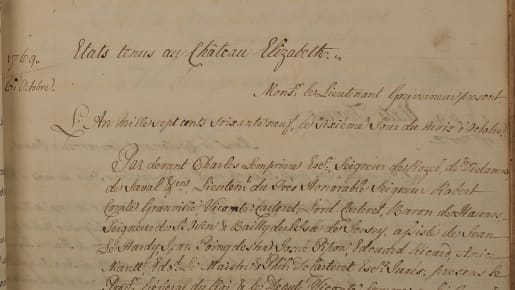

Privy Council record book recording the meeting held at Elizabeth Castle

Tom Gruchy

Tom Gruchy led the main group of protestors from Trinity during the 1769 Corn Riots. He may have been influenced by revolutionary political ideas from America where he lived for many years.

As a young man, Gruchy had emigrated to America where he married Mary Dumaresq and prospered. He made his fortune in Boston as the owner and commander of a British privateer and as a smuggler. He and his wife lived in a grand house and kept an enslaved black girl called Tamuse as their servant. When his fortune was lost, he returned to Jersey where he became a churchwarden and parish official in Trinity.

At one Parish Assembly he was reported as reading out a list of reforms and warning of a potential revolt if the demands of the people were not listened to.

Law and order

Colonel Rudolph Bentinck, a Dutchman, was sent to the Island with five companies of soldiers in order to bring peace after the Corn Riots and to start an investigation. He discovered that the situation was not as serious as had been reported but immediate changes were still put in place. It was once again made illegal to export crops and a committee was set up to examine the distribution of grain. In 1770 Bentinck was named Lieutenant-Governor which gave him even more authority.

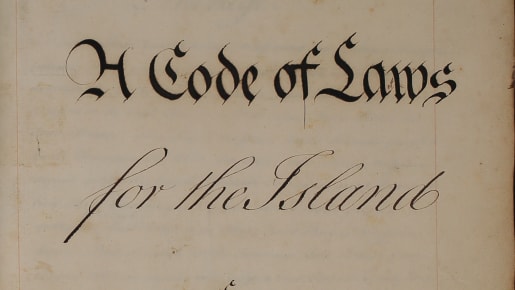

The Code of Laws of 1771

In September 1770, Bentinck declared that a set of rules and regulations be written down to make the Law as fair as possible. The aim was that everyone ‘…be no more obliged to Live in a continual dread of becoming liable to punishments, for disobeying Laws it was morally impossible for them to have the least knowledge of.’

Bentinck’s Code was introduced in 1771 and clearly laid down the Laws of the Island. It also divided the power to make the laws and enforce the laws between the States of Jersey and the Royal Court. Charles Lemprière remained as Lieutenant Bailiff but he had lost his monopoly on power.

The Corn Riots had started Jersey on the road to reform and a fairer society.

Manuscript of the Code of Laws of 1771