The Occupation of the Channel Islands by the French during the Wars of the Roses in the 15th Century

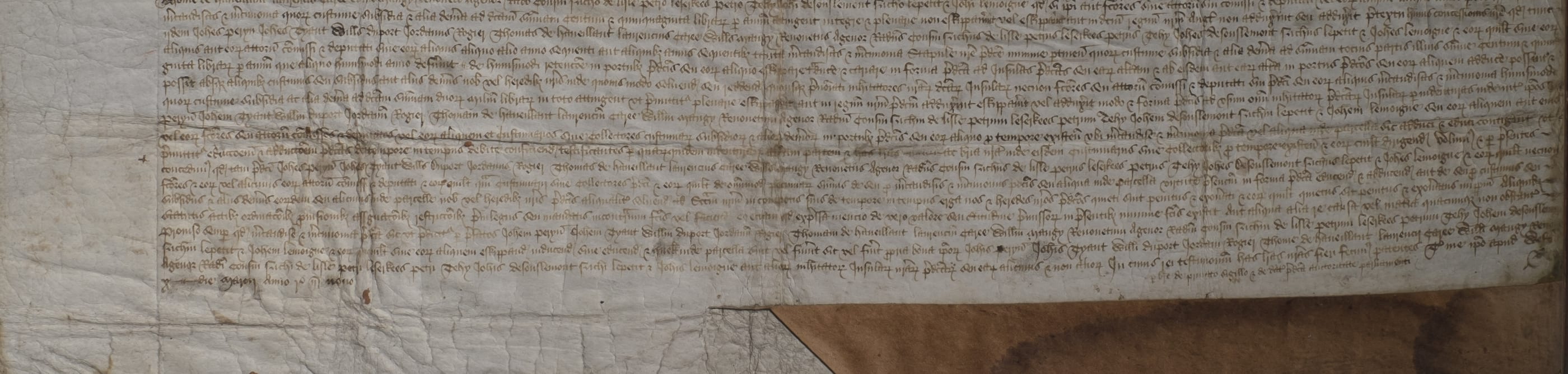

A document from the 15th century held at Jersey Archive, after being purchased by the Crown for the Island in 2011, shows the importance of trade to the Islanders and highlights the Occupation of the Channel Islands by the French during the Wars of the Roses in the 15th Century.

The document is from Edward IV to the people of Jersey and is dated 10th March 1469. Edward IV was a warrior King, living in a time of bloody battles and civil war. He was 6ft 3” tall, well-built and handsome. He fought for and won the English throne at the age of only 18. Edward could also be a charming, affable man who married an impoverished, Lancastrian widow against the advice of his council and had a number of mistresses.

Edward was proclaimed King on 4th March 1461 as the head of the Yorkist cause. His claim was strengthened by the decisive Battle of Towton on 29th March 1461 which was the largest and bloodiest battle ever fought on English soil, according to reports from the time 28,000 men died on the battlefield.

The Lancastrian nobility suffered heavy losses at Towton and their King, Henry VI fled into exile in Scotland and then France with his wife, Marguerite of Anjou and his son.

Edward spent the next eight years consolidating his grip on the English throne, however, after alienating his former ally and one of the most powerful nobles of the realm, the Earl of Warwick, Edward found himself once again plunged into battle for his kingdom.

On 26th July 1469 the Battle of Edgecote Moor took place in which Warwick rebelled against the Crown alongside Edward’s younger brother George, Duke of Clarence. Edward wasn’t with the Yorkist forces at the battle but was captured shortly afterwards in August 1469 at Olney.

Edward was released when other members of the nobility organised a counter-rebellion. He did not punish Warwick and his brother George who subsequently rebelled again in 1470 and had to flee for France. Once in France Warwick made an alliance with the Lancastrian forces and with the support of the French invaded England in September 1470.

Edward was forced to flee the country leaving on 2nd October 1470 for Burgundy. He was deposed as King of England on 03/10/1470. Edward became the only deposed Monarch to win back his Crown when he landed back in England in 1471 winning the Battle of Barnet on Easter Sunday in April of the same year.

Jersey and the Wars of the Roses

Around the very time when Edward’s English throne was secure after his coronation Jersey came under threat. In the spring 1461 Mont Orgueil Castle was raided by a French Force under Jean Carbonnel, cousin of Pierre de Brézé, Comte de Maulevrier who himself was the first cousin of Marguerite of Anjou, the Lancastrian Queen.

The French took Mont Orgueil by surprise. There was suspicion of a betrayal by the forces at the Castle as a postern gate was left open and the guards were plied with drink, allowing the French to take the Castle with relative ease.

The French remained in charge of the Island until, in 1468 Richard Harliston, a Yorkist Vice-Admiral dedicated to the cause of Edward IV secretly landed on the Island and met with Philippe de Carteret, Seigneur of St Ouen. de Carteret was a leading figure of resistance against the French Occupation.

Harliston and de Carteret mustered local troops and laid siege to the French forces at Mont Orgueil on 17th May 1468. The French were running short of supplies after 19 weeks but a St Malo boat, La Jehanette, ran the English blockade bringing much needed goods to the French garrison.

Despite the additional provisions the siege only lasted for just over 6 months until the Castle finally had to surrender and the Island was reclaimed for the England Crown.

On 28th January 1469 Edward IV confirmed all Jersey’s ancient franchises and gave the people of Jersey freedom from charges made in cities in England:

‘bearing in mind with what constancy and courage the community has proved loyal to us and our forefathers and how many perils and losses they have borne in reducing our Castle of Mont Orgill’

The document at Jersey Archive adds a more personal facet to the story and gives us the names of some of the Islanders of the time. We know that when Edward IV regained the Islands he recognised the loyalty of Jerseymen and the dangers and losses they had suffered.

The document, which is enrolled on the Calendar of Close Rolls now seems to indicate that Edward, despite praising the ‘great fealty’ of the inhabitants of Jersey expects compensation from the Channel Islands of the sum of £2,833 6 shillings 8 pence for the

‘re-taking of our said Island of Jersey and Castle of Mont Orgueil on the same Island’.

This is a tremendous sum of money given that Jersey was recovering from the effects of occupation – the equivalent worth today is reckoned at £1.4 million.

However, Edward does offer trade incentives to Islanders which he hopes will help them pay the compensation.

Edward shows his concern that this sum will lead to the ‘manifest impoverishment’ of the people of the Islands unless they are ‘by us the same be aided’. He talks of the ‘great fealty’ that the Island have shown the Crown and to assist with the payment of the recompense by the Islands he uses this document to establish a grant to the following individuals:

- John Peryn

- John Tyant

- William Duport

- Jordan Rogier

- Thomas de Haveillant

- Laurence Caree

- William Maugy

- Renouet Agenor

- Ralph Cousin

- Nicholas de Lisle

- Peter Leserkees

- Peter Tehy

- John Desouslemont

- Nicholas Lepetit

- John Lemoigne

The grant gives these people or their representatives the right to trade their own goods and also those of other Islanders as follows;

‘so much, so many and so great trades and buying’s whatsoever of our Staple of Calais, in the least degree pertaining, within our Kingdom of England, (to) themself, and to provide for and the same thus gaining and provided for, in whatsoever ship…….from our homage at one time or diverse times in our ports of Poole, Exeter and Dartmouth….’

Although a community of English merchants concerned with the export trade existed before this time, the Company of the Staple can be confidently traced back to 1359, when the first royal grant was issued giving the merchants unequivocal control of the export trade in staple commodities. In 1363 the “Community of the Merchant of the Staples” moved to Calais from Bruges and soon became known as the Mayor and Company of the Merchants of the Staple of England.

In order to ship wool to Calais a merchant had to be a member of the Company and to obey its ordinances. Admission could be gained through a three to four-year apprenticeship or by purchase and by the end of the fifteenth century, nearly 400 men were members. The Company enjoyed great wealth and controlled the English wool trade until the loss of Calais in 1558, by which time changes in the English textile industry were also undermining their trade.

If the Islanders find that they have £150 each year over, after paying customary dues and costs this money is to be paid towards the recompense.

This type of grant seems to be in keeping with Edward’s own trading ambitions. Against the picture of a warrior King we also have a man who tried to improve the efficiency and profitability of the English administrative system resulting in him being one of the few medieval Kings to die solvent.

Edward built closer relations with the merchant community and encouraged commercial treaties. He successfully traded wool on his own account to restore his family’s fortunes and thus freeing him from dependence on subsidies from Parliament. Through this document he appears to be encouraging the people of Jersey to do the same.