This ancient language has woven itself into the fabric of Jersey’s identity, its vocabulary is shaped by the Island’s landscape, agricultural and seafaring traditions

For centuries, Jèrriais has been the language of Jersey. It is the Island’s indigenous tongue; a Romance language closely related to the Norman French spoken by William the Conqueror when he claimed victory at the Battle of Hastings in 1066. This ancient language has woven itself into the fabric of Jersey’s identity, much like the castles and fortifications that dot its coastline. Its vocabulary is shaped by the Island’s landscape, agricultural and seafaring traditions.

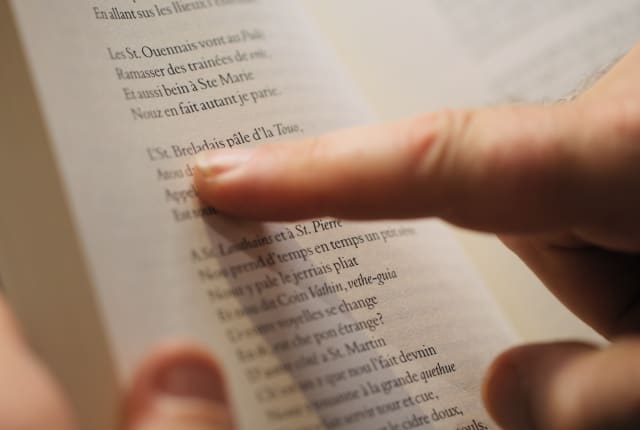

Jèrriais is not just a relic of the past; it is a living connection to the Island’s history and the language’s resilience is remarkable. Despite the rise of English and French, Jèrriais has persisted, passed down through generations as the language of the common people, of farmers and fishermen, of storytellers and poets.

Yet, like the old castles that have withstood the test of time, Jèrriais has faced its own battles. The 20th century brought significant challenges as English became dominant, especially after the Occupation of Jersey during World War II. The number of Jèrriais speakers dwindled as the younger generations embraced English, drawn by its global reach and modern appeal.

In recent years, however, there has been a renaissance of interest in Jèrriais. Efforts have been made to revive the language, with schools offering lessons, and cultural organisations promoting its use. Jèrriais is now recognised as a key part of Jersey’s intangible cultural heritage and an official language of the Island, and there is growing appreciation for its importance in maintaining the Island’s unique identity.

Much like Mont Orgueil (Lé Vièr Châté) and Elizabeth Castle (Lé Châté Lizâbé), Jèrriais is a symbol of Jersey’s endurance and resilience. It is a reminder of the Island’s rich history and its capacity to adapt and survive through changing times. Today, as the language experiences a revival, it continues to be a vital part of what makes Jersey distinct—a testament to the Island’s enduring spirit and its deep-rooted connection to the past.