The Channel Islands have been described as ‘proportionate to their size, the witch hunting capital of Atlantic Europe.’

By the early 1500s outbreaks of witchcraft panic with mass executions spread throughout Europe. Over the 160 years from 1500 to 1660 Europe saw between 50,000 and 80,000 witches executed. About 80% of those executed were women.

The Channel Islands have been described as ‘proportionate to their size, the witch hunting capital of Atlantic Europe.’ Between the 1560s and 1660s, when the Island had a population of around10,000, there were at least 65 witch trials that came before Jersey’s Royal Court with 33 leading to execution and eight to banishment. Perhaps unsurprisingly 88% or 57 of those named as witches in Jersey and placed before the Royal Court were women.

The process of bringing individuals to trial in Jersey either required a confession, proof ‘as clear as day’ or a parish indictment with parishioners deciding whether there was a case to answer. If there was a case to answer then the accused was invited to submit to an inquiry by 24 men with a 5/6ths majority required for a guilty conviction punishable by death.

Whilst waiting for a confession or inquiry the accused could be held in prison for up to a year and a day. If found guilty, it was common practice in Jersey to hang those accused of witchcraft and then burn the body rather than burn the individual alive, a small mercy.

The records of the witch trials in Jersey are preserved in the registers of Cour du Cattel a division of the Royal Court that dealt with criminal cases until the late 18th century.

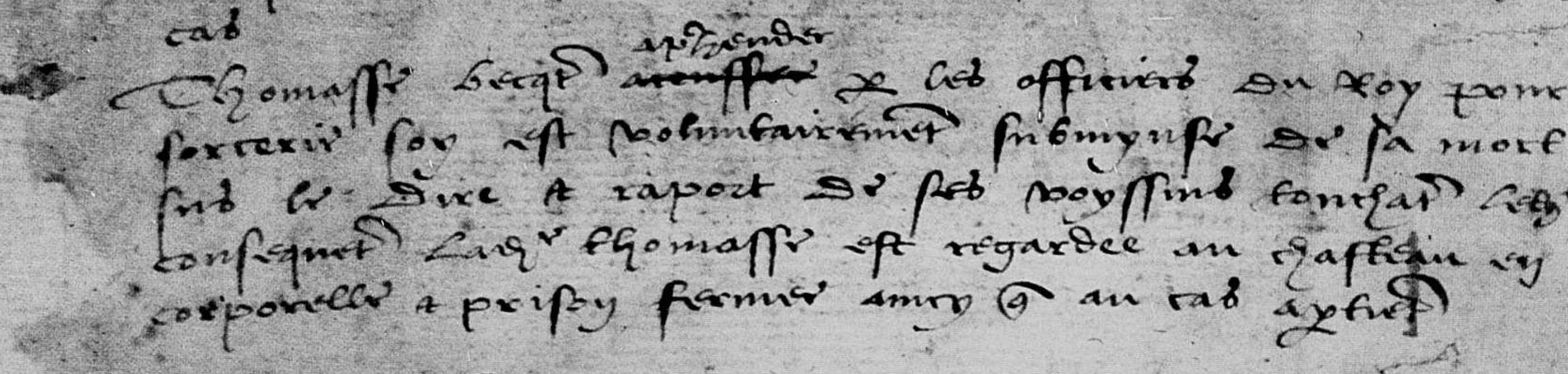

The first case to be found in the registers is that of Thomasse Becquet. Thomasse was apprehended by the Officers of the Crown on the accusation of being a witch in 1563. She was locked in Mont Orgueil Castle. Thomasse was eventually discharged following the inquest into her crime.

Trial of Thomasse Becquet

During the early 1580s the plague spread to Jersey. On 25 September 1584 Jersey’s Island Church Assembly noted that persons who were ill, or had an illness in the family, who resorted to consulting with witches should be called before the parish church court to be censured.

The Church Assembly were effectively putting in place a mechanism to censure those who consulted people seeking a cure for their friends or family using non-conventional means.

It is clear that there was a link between outbreaks of plague in Jersey and witch trials. In late 1585 we see a cluster of executions in Jersey with four women and one man executed for witchcraft in November and December of that year.

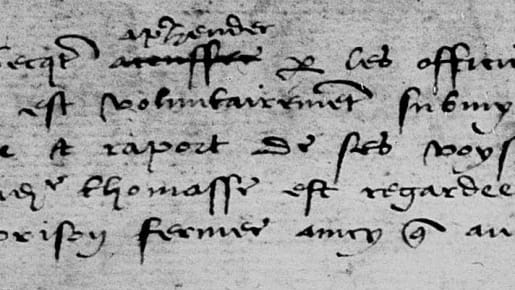

The link between those who were seen as potential witches at the time and who we might now see as healers is shown in the trial of Jeanne Le Vesconte who was accused of the diabolical crime of witchcraft.

‘infecting some and curing others.’

Jeanne was tried in November 1585 and was executed at St Ouen. Jeanne’s trial is the first entry that we see in the books of the Cour de Cattel in which the accused was condemned to death. The extract from the court books shows that she had been accused of the diabolical art of witchcraft, always carrying out evil spells and employing her arts towards both people and their property.

Trail of Jeanne Le Vesconte

The next outbreak of plague in Jersey took place in 1591 and again Jersey’s Church Assembly resolved that any of those who were sick or had family who were sick and resorted to consulting witches should be excommunicated.

On 23 December 1591 the Royal Court in Jersey ordered that any person who consulted with witches or soothsayers when afflicted was as guilty as those who they consulted and so anyone consulting with a witch should be suspected of being one too.

Five people were tried for the crime of sorcery between October and December 1591, four were executed and one, Collas Alexandre, who had been arrested alongside his father Michiel was acquitted.

Those executed included Symon Vauldin of St Brelade. The account of Symon’s trial shows that he confessed to his crimes which included having familiar communication with the devil in the different forms of a cat and a crow.

The account shows that Symon had long been suspected of the crime of witchcraft and that he was condemned to death by an inquiry of 24 men who found that he was a witch with a wicked and unstable life. Symon was condemned to be strangled and then his body to be burned and reduced to ashes with all his goods to be confiscated and claimed by the Crown.

June 1648 saw at least six people charged with the crime of witchcraft in the courts. This compares to just two cases in the whole of the 1630s and 1650s with the previous case being brought to the courts 17 years earlier in 1631.

In England the 1640s and 1650s were an intense period of witch trials and hunts, set against the Civil War and Puritan era. Whilst Jersey was still loyal to the Royalist cause in 1648 it appears that this background had an impact on the number of trials in the Island.

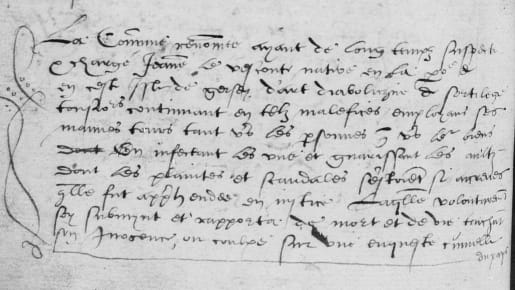

Marie Esnouf was one of those charged, she was born in St John in 1604, the daughter of Noé Esnouf and his wife Marie, her Grandfather had been the Rector of the Parish so we can assume that she came from a respectable family. She married Jean Le Cerf and the couple had four children between 1625 and 1630.

Marie’s court records from 1648 show that she had been imprisoned in Mont Orgueil Castle as she refused to confess to the crime of sorcery. She was imprisoned after a number of people had testified that she had used her diabolical spells to cause the deaths and illness of several humans and beasts.

As we have seen, the process of bringing individuals to trial in Jersey either required a confession, proof ‘as clear as day’ or a parish indictment with parishioners deciding whether there was a case to answer.

In Marie’s case the parishioners clearly testified that there was a case and so she was required to submit to an inquiry by 24 men with a 5/6ths majority required for a guilty conviction punishable by death.

The court records show that enough of the 24 thought that Marie was guilty and she was sentenced as follows;

‘To be taken from here to the place of execution and the execution post erected for this purpose, to be hanged and strangled by the hands of the executioner, resulting in death and subsequently her body to be burnt by fire and reduced to ashes.’

Marie’s execution is described in Jean Chevalier’s diary and was obviously a public spectacle. Chevalier recounts that the town was filled to overflowing and that there had not been such as crowd since the Prince [later Charles II] came to Jersey.

His diary indicates that Marie was charged with ‘detestable things’ by over 60 witnesses and that she was found to have the witches mark [a black mark] on her palate. Marie was put to death in the Market Place, now the Royal Square.

‘The churchyard walls and the Town Hill were thronged with men and women, lads and girls. Such crowds had not been seen since the Prince came to Jersey. She too denied her guilt, but refused to submit to the Enquête, and was kept a long time a prisoner in the Castle. When at last she yielded, more than sixty witnesses “charged her with villainous and detestable things, and a black mark was found on her palate. The jury was not unanimous, but twenty considered her guilty, and she was put to death in the Market Place…’

The period 1648 to 1650 appears to be the last time that there were multiple witch trials in close succession in Jersey. Single trials have been found in 1656, 1660 and 1661 but it would appear that, in common with the rest of Europe, the height of the witch trials was over.