For most of the Second World War (from 30 June 1940 until Liberation on 9 May 1945) the Channel Islands were occupied by forces of Hitler’s Nazi Germany. Fortifications were built as part of Hitler’s ‘Atlantic Wall’ by thousands of forced workers brought over from the Continent. For many people in Jersey today the Second World War is still referred to as ‘The Occupation’. Although there is physical evidence left from this period – the fortifications that can still be seen on our coastline – for details of the lives of people during this time we can reach into archives like the Occupation Registration Cards, part of the Jersey Heritage Collection.

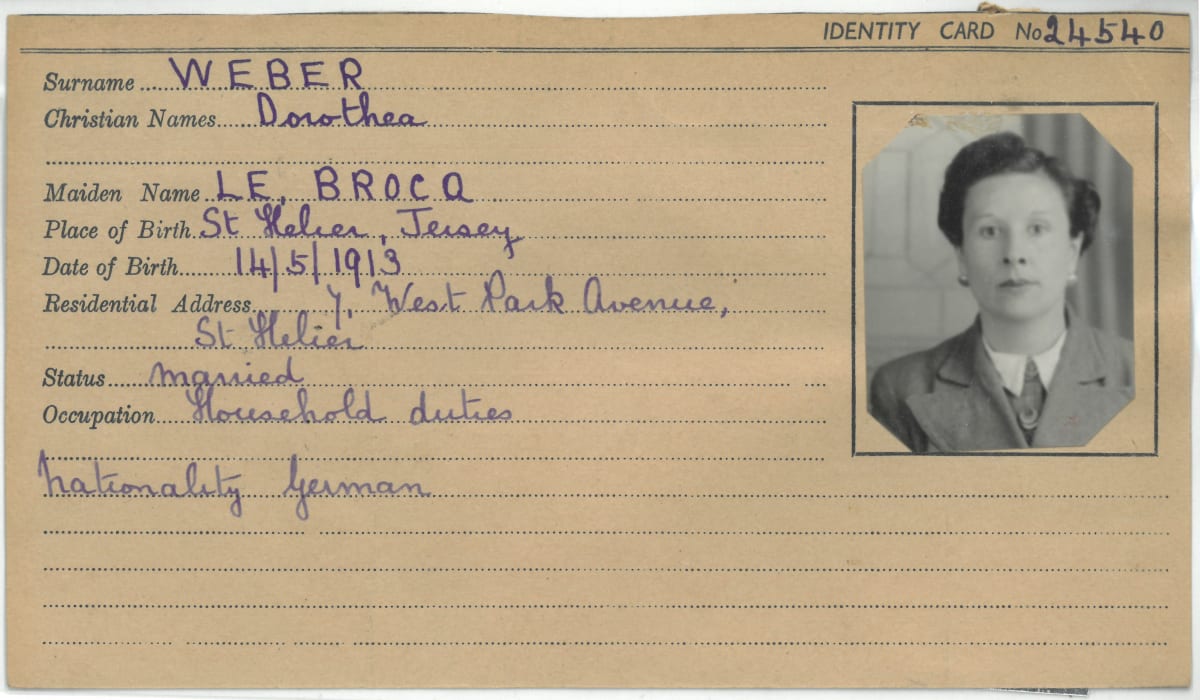

In 1940 the whole civilian population of Jersey were required to register by the German authorities, a decision to try to control the movement of Islanders. Under the Registration and Identification of Person (Jersey) Order over 31,000 people registered. Recognised by UNESCO, this archive is a good place to start your family history research. New stories are always being unearthed about the Occupation. And as details emerge, new heroes and heroines of the period can be named. One such person is Dorothea Le Brocq, born on 14 May 1911. She was working as a clerk and living with her mother in St Helier at the time of the Occupation. In May 1941 she married Anton Weber, an Austrian baker who had arrived in the Island in 1938 – probably fleeing his home country to escape conscription. Dorothea acquired German nationality as a result of her marriage. To the best of our knowledge, Dorothea lived alone at 7 West Park Avenue after Anton Weber was forcibly drafted into the German army and left the Island in 1944.

We don’t have details of Dorothea’s day to day life but we know she took in a Jewish woman called Hedwig Bercu and sheltered her, away from the German authorities. Born in Vienna on 23 June 1919, Hedwig Bercu arrived in Jersey from Austria (via England) in November 1938. She was 19 – a young refugee from persecution. We think Dorothea sheltered Hedwig out of kindness. As Hedwig arrived in Jersey as a domestic worker, it is unlikely that she was a woman of independent means who could pay Dorothea to shelter her. It is not known whether Hedwig and Dorothea knew each other before Dorothea took Hedwig into her home. It is possible that after marrying Anton Weber, Dorothea may have been trusted by the German authorities enough to work in the same office as Hedwig and may have known her that way.

By 1940 Hedwig had become categorised as a ‘registered Jew’. Despite this, Hedwig obtained employment in Jersey as an interpreter at the transport department of Organisation Todt, the paramilitary engineering organisation which was responsible for bringing thousands of forced and slave labourers to the Channel Islands to build the Atlantic Wall. In this job Hedwig had access to petrol coupons which she secretly took for distribution to Jersey doctors so that they could visit their sick patients. Someone discovered what she was doing and threatened to inform on her, which triggered her decision to go into hiding but first she decided to fake her own suicide by leaving some clothes with a note on the beach. On 22 and 23 November 1943 a wanted notice for Hedwig was published in the local paper, the Evening Post.

Hedwig had first been hidden by Bozena Kotyzova, a Czech woman who had been employed as a housemaid and was now living alone in a large house. But shortly afterwards, Hedwig moved in to Dorothea’s home, a narrow, terraced house in the middle of Town. She remained concealed there for 18 months until the Liberation of the Channel Islands in May 1945. At 4.30pm on 14 May 1945, Hedwig reported herself to Jersey’s Aliens Office as having been hiding in secret with Dorothea for the last 18 months. During her time at Dorothea’s she was secretly helped by a German officer who brought food to the two women. His name was Kurt Rümmele and Hedwig would go on to marry him. After the Liberation Hedwig stayed on in Jersey for a few more years, working as a nanny for the local family for whom she had worked prior to the Occupation.

It seems that Dorothea Weber and Hedwig Bercu then lost touch. Having no contact with her husband Anton, Dorothea made enquiries of the German authorities, who informed her that her husband was dead. On 23 August 1945, Dorothea Weber married Francis Flanagan, one of the British soldiers who had liberated the Island a few months earlier, and they moved to England. But her first husband, Anton Weber, actually lived out the war in a Russian prisoner-of-war camp. In 1949 Dorothea and Francis were both brought back to the Island to stand trial for bigamy. Dorothea, an unwitting bigamist, was given a six-month suspended sentence. Dorothea returned to England after the ignominy of the trial but very little is known about the rest of her life. She died in May 1993, aged 82, and her ashes were scattered in the memorial gardens of Worthing.

Sadly, the two women never met again after 18 months of living at such close quarters and in such stressful and dangerous conditions. Dorothea had risked her life to shelter Hedwig. Had she been caught, then it is likely that she would have been sent to a concentration camp. In 1989, Hedwig made an emotional tribute to the woman who had saved her life: ‘[Dorothea] was certainly one of those who risked her life to save and help others who couldn’t help themselves and were in great need. Unfortunately, we lost contact when we left the Island, but we will never forget her and the great risks she took on our behalf. With gratitude we remember her sacrifice, and say thank you, Dorothy, from all our hearts. We survived only through your help and courage.’

In November 2016, in a moving ceremony at the Occupation Tapestry Gallery, Dorothea Weber, née Le Brocq, was posthumously recognised as ‘Righteous Among the Nations’ by Yad Vashem, the State of Israel’s National Holocaust Memorial, for having saved the life of Hedwig Bercu.