Records opened to the public after 100 years give an insight into life in Jersey at the beginning of 1920s, with changing attitudes towards education making an impact on Islanders’ lives.

Records opened to the public after 100 years give an insight into life in Jersey at the beginning of 1920s, with changing attitudes towards education making an impact on Islanders’ lives.The records, which are stored at Jersey Archive, date from 1921 and were officially opened to the public on 1 January 2022. They include the minutes of the Elementary Education Committee, an Honorary Police Arrest Register and the Annual Admissions to the Jersey General Hospital.

They are from a year when, despite the optimistic start to the roaring ‘20s, unemployment in the UK reached a post-war high of 2.5 million as demobilised soldiers found it increasingly difficult to get jobs. The UK Education Act raised the school leaving age to 14 and developments in education were reflected in Jersey.

Linda Romeril, Jersey Heritage’s Director of Archives & Collections said: “Each year, new records are released to the public after closures of up to 100 years under Freedom of Information exemptions. This year’s records include both stories of individuals and of wider social policies and attitudes in the 1920s.

“It is always fascinating to see the changes in our lives that have occurred over the past 100 years. The records released this year show the growing importance of education for all children, changing attitudes towards male and female wages, crime and punishment in the 1920s and, interestingly in our current climate, the impact of vaccination programmes on diseases such as Diphtheria.”

- A free talk about the newly-opened records takes place on Saturday, 15 January at 10am at Jersey Archive. Places are limited and can be booked by calling 833300 or emailing archives@jerseyheritage.org.

Elementary Education Committee Minute book for 1906 – 1921

One of the records opened to the public which gives an overview of the development of children’s education in Jersey is the Elementary Education Committee Minute book for 1906 – 1921.

Entries on the first page of the Committee Minute book show the range of matters that were considered by the Committee. At their meeting on 26 November 1906, the Committee discussed the dates for the Christmas holidays, 24 December to 12 January; a letter to the head teacher of St Paul’s boys’ school to concerning the teaching of French; and a letter from the Board of Education stating that St Martin’s Roman Catholic school had not been certified as efficient by the Board’s inspector.

It was only in 1894 that elementary education became compulsory for all children in Jersey aged between five and 12. However, at this point exemptions were granted to children who lived more than two miles from a school and this caused problems within parishes where parochial schools had not yet been established.

In 1899, legislation was passed that required each parish to provide a parochial school and also to form an elected Conseil Paroissial, who monitored attendance. Once this legislation was introduced, nine parochial schools were built.

The increased number of schools in the Island led to the need for more teachers. The Elementary Education Committee often discussed the pupil teachers’ central classes and on 8 July 1907, they nominated Elsie Bowers, Jennie Leslie Gale and Lydia Pallot to go for interviews at the Salisbury Diocesan Training College.

The young women were to be interviewed for the two places that had been assigned at the college for trainees from Jersey. Evidence in later documents shows that all three went on to become teachers in Jersey schools.

In 1909, new legislation on Primary Education was passed by the States. However, this legislation took over three years to be approved by the Privy Council following petitions sent to the Crown.

In their meeting in February 1911, the Elementary Education Committee mentioned the petitions that were blocking the law and the Committee found that the amount of time it was taking for the law to be passed was making it difficult to administer the schools effectively, which in turn was very disadvantageous to the children being taught.

The law was eventually passed in 1912 and it meant that all parochial schools came under the direct supervision of the States. Church schools, which had previously been subsidised by the States, could also apply to come under the new law as long as they were certified as ‘efficient’ by the school board inspectors.

The impact of the 1912 law can be seen in the Committee’s January meeting in 1913. Under the new law, the Committee approved a syllabus for religious instructions and also adopted rules concerning the teaching of the French language in primary schools.

Salaries also featured in the minutes of the committee from May 1918 and show the significant changes in attitudes toward equal pay for men and women that have taken place over the last 100 years.

The scale of salaries shows head teacher salaries subdivided by school type, which appears to be based on pupil numbers, with the highest salaries for those heading up schools with over 200 pupils.

The salaries are then split between men and women. A male head teacher of this size of school would earn £190 – £260, while a female teacher of exactly the same school and in exactly the same position would earn £150 – £220.

Honorary Police Register, St Helier 1920-1921

The Arrest Registers from the Honorary Police provide an insight into crime and punishment in the Island 100 years ago. The crimes recorded range from youthful misdemeanours to more serious crimes of assault and abandonment.

The following arrests were all made by the officers of St Helier during the period 1920 – 1921.

On 12 February 1920, a group of young boys were arrested by Francis Valpy. The boys were Leonard Richard Planner, age 12, originally from London; Victor Morin, age 13, from St Martin; Thomas Marry, age 12, from St Helier; and Auguste Ravily, age 13, and also from St Helier.

The four boys were accused of stealing goods from a number of shops in St Helier, including a pound of butter from a shop in Halkett Street and a pot of jam and some cigarette papers from John Tregear’s shop in King Street.

The Honorary Police Register records that all the boys were freed that same day after appearing before the Police Court, with the ringleader of the gang appearing to be Leonard Richard Planner.

On the day before the boys were arrested, Leonard was admitted to the Jersey General Hospital for reasons of indigence or poverty. Leonard is listed as a 12-year-old from London but the name of his father is left blank. The register shows that Leonard left the hospital and went into police custody on 12 February.

Leonard was a pupil at La Motte Street Boys School and in May 1921, the head teacher’s log book records that he was one of three pupils to be granted an exemption from attendance at school for six weeks. An entry in the same register, from June 1921, shows that Leonard was granted an exemption as he was working as an errand boy for the Co-operative Society.

On 23 February 1920, the residents and shop owners of King Street were alarmed by a motor bike being driven dangerously up the road by 19-year-old Francis Philip Le Rendu. Francis was fined £4 by the court.

On 8 April 1920, John Stafford, alias John J Ross, was arrested for committing a fraud against George Duval by issuing him with a cheque for £10 under the signature John J Ross. The cheque proved to be worthless and John was sent to the Royal Court for sentencing. At the time of his arrest, John was 21 years old and the Honorary Police Register shows that he was a native of London. He was sentenced to three months hard labour.

On April 10 1920, Charles Edward Tostevin of St Helier, aged 51, was arrested. Charles was charged with refusing to maintain his wife, Amanda Brück, and their four children, Clarence Charles, who was 5; Raymond Henry, aged 4; Vernon Edward, aged 18 months; and Amanda, who was just eight months old. Amanda and her children had fallen upon the charge of the Parish of St Helier. Charles was liberated from prison and no further action appears to have taken.

Charles and Amanda were both widowers when they married in May 1912. Charles was 42 and Amanda 35. This entry is not uncommon in the arrests register with a number of men arrested for failing to support their families.

On 8 November 1920, Alice Downer, the wife of George Fox, aged 48, was arrested for grossly insulting Mary Ann Coutanche, widow de la Haye, at Highlands, Mont Cochon. The nature of the insults went on to cause a disturbance of the public peace. The case was taken to the courts and the ladies were bound over to keep the peace towards each other.

On 10 February 1921, in an extremely unusual case, Alfred Francis John Malzard, aged 51, was arrested. The Honorary Police Register states that on 9 February at the Mitre Hotel in Broad Street, he obtained a tiger skin from Mohammed Ber Ali Assam for which he should have paid £2.

The sum was not paid and so the police arrested Malzard for stealing the tiger skin from Assam. The matter went before the Police Court and Malzard was required to pay a fine of £2 or, in default of payment, to be sentenced to 15 days in prison. It is not clear what eventually happened to the tiger skin!

Jersey General Hospital Admission Register 1921

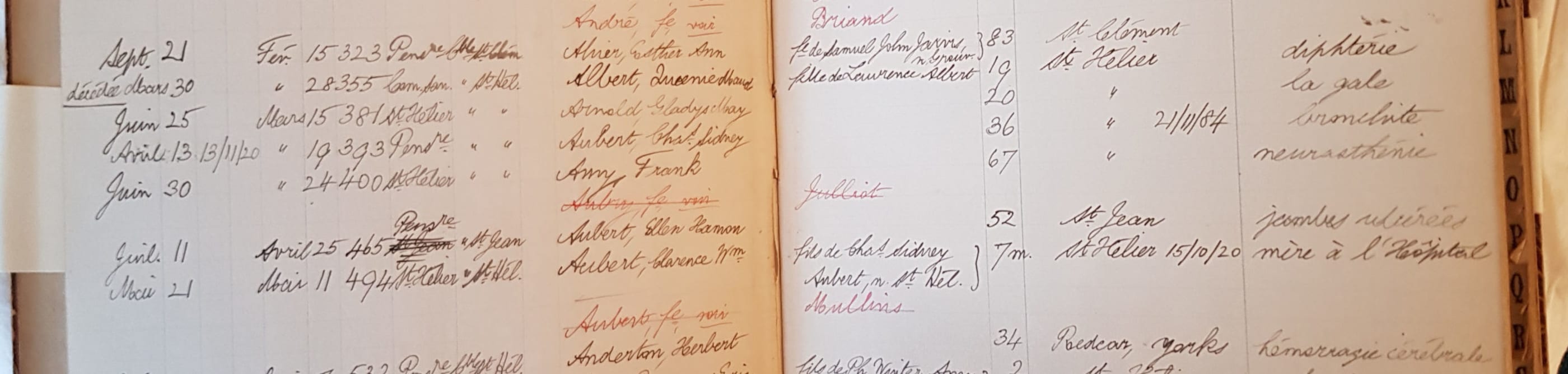

The Jersey General Hospital Admission Register for 1921 shows the names, place and date of birth, date of entry and reason of admission to the Jersey General Hospital. The records are an excellent source for family historians and also show the principal reasons for individuals being admitted to the hospital.

Analysis of the first 140 entries in the Admission Register shows that the greatest cause of admission was Diphtheria. Of the 20 people admitted to the hospital for this reason, 14 were under the age of 18 and the youngest was three-year-old Arthur Bliaut. Those admitted also included nine-year-old Jack Edward Brown and records show that he was born in Australia. Diphtheria was a major threat to children during the 19th and 20th centuries and was the target of the first major vaccination programme in children in the UK in 1940.

Bailiff’s Incoming Correspondence 1919 – 1921

The Bailiff’s incoming correspondence file of letters from 1919 – 1921 covers a number of subjects that arose in the Island following the end of the First World War. This includes correspondence about the diagnosis and treatment of venereal disease in the Channel Islands and the introduction of the legislation regarding unemployment.

The letters also show the growing importance of the Royal Air Force following the First World War. In April 1920, the Air Ministry sent out a circular concerning the entry of Boy Mechanics to the Royal Air Force.

On a more local front, in June 1920, the Jersey Defence Committee reviewed the Militia Law of 1905 and proposed several modifications in light of the experience of the First World War.

The new scheme proposed that the Active Militia strength should not exceed 1,000 men of all ranks, organised into a Company of Garrison Artillery and four Companies of Infantry. The scheme also proposed that all men who were 18 and over when the law came into force would be exempt from Militia service, with boys of 16 and above being liable for preparatory service, which consisted of 36 drills per year.

Service on the active list would not exceed five years and on completion of the service, the individual would then be placed on the reserve list until he was 35.

The proposed Militia Law did not meet with universal approval and the Bailiff’s files include a letter from the Jersey Preparative Meeting of the Society of Friends asking the States to reconsider compulsory military service in the Island.