Archive records opened to the public – some after being closed for 100 years – have given fresh insight into what life was like for Islanders in the years between the two World Wars

The documents, released under the Freedom of Information Law, shine a light on the assistance given to Islanders in need; how the General Hospital was run; crime and punishment in St Helier, including a court case involving a young Alexander Coutanche, who would go on to become Bailiff; and the impact of Nazi Germany on people who were applying to come to the Island, including Jewish families desperate to leave occupied territory.

Carefully stored at Jersey Archive, the records were officially opened to the public on 1 January 2023. They include the minutes of the Public Assistance Committee, Police Arrest Registers from St Helier and applications to the Alien’s Office from a family living in annexed Austria in 1938.

Many of the records date from 1922, a year when the Irish Free State was created under the Anglo-Irish Treaty, ending the three-year Irish War of Independence; the BBC was formed in October; and on 4 November, Howard Carter and his men found the entrance to Tutankhamun’s tomb. In Jersey, the States were discussing the increase in unemployment amongst demobilised soldiers, the transfer of Elizabeth Castle from the Crown to the States of Jersey and the transfer of the care of Overdale Hospital to the Hospital Committee.

Linda Romeril, Jersey Heritage’s Director of Archives & Collections, said: “Each year, new records are released to the public after closures of up to 100 years under Freedom of Information exemptions. This year’s records include both stories of individuals and of wider social policies and attitudes in the inter-war period.

“It is always fascinating to see the changes in our lives that have occurred over the past 100 years. The records released this year show the dual role of the General Hospital as a place for those with medical needs and as a poor house, the different types of crimes that were committed in Jersey in the early 1920s and the impact of the rise of Nazi Germany on Island policies.”

- A free talk about the newly-opened records takes place on Saturday, 21 January at 10am at Jersey Archive. Places can be booked by calling 833300 or emailing archives@jerseyheritage.org.

Acts of the Public Assistance Committee, 6 August 1918 – 6 March 1922

The Public Assistance Committee was created in 1906 and assumed responsibilities for the administration of public assistance and the running of the General Hospital. The Committee was responsible for the internal poor, those resident in the General Hospital for reasons of poverty rather than illness, and the external poor, who were given monthly pensions but not taken into the hospital.

The General Hospital also operated as a place for sick people and the Public Assistance Committee were responsible for appointing staff to work at the hospital, approving the accounts and payment of suppliers.

The Committee Meeting of 6 August 1918 gives an overview of the work of the Committee and the stories of the some of the people who they helped.

The first business for the Committee was the award of a monthly pension of £1 to Adele Brochard, who was 79 and described as a native of France. Adele was the widow of Pierre Le Blond and had lived in Jersey for about 67 years.

The Secretary then reported to the Committee that Edouard Perree had been admitted into the General Hospital on 3 May 1918. Edouard had previously received a monthly pension and his household goods had been sold for £11 15s. This sum was given to the Treasurer of the States with the instruction that it go into the account for helping the external poor. Edouard was 86 when he entered the hospital with a dislocated shoulder and he remained there for a further nine years until he died at the age of 95.

The Committee then reimbursed Miss Wheatley from the House of Help for her travel expenses of £3 3s to go to the wedding of Hilda Renault, aged 19 from St Helier. Hilda was the illegitimate daughter of Jane Renault and was marrying John Johnson at St Faith’s Home, Lostwithiel, Cornwall.

The Committee also dealt with staff matters and appointed Kate Shaw as a Staff Nurse, receiving a salary of £34 per year.

The Committee ended the meeting by reviewing the number of internal poor at the hospital and there were 231 registered at the end of June 1918. During the month of July, there were 43 admissions of internal poor to the hospital, with 35 leaving and five deaths. This left a total of 234 individuals at the end of the month. The number of visitors to the internal poor were also monitored, with 1,376 over a 13-day period.

In March 1921 a report is presented to the Committee on the medical service and general administration of the hospital. The report has been written by a sub-Committee, established in 1920 to look into these matters. The report gives a useful overview of the medical service at the hospital.

Up until 1912, the medical care of the inmates in the hospital was in the hands of one medical man, appointed by the States, who visited the institution daily but only spent part of his time on this work. In 1912, a Resident Medical Officer was appointed by the States and Dr Alexander B Voisin was put in post. Dr Falla was appointed as his assistant shortly after. In 1916 Dr Voisin died and, due to the circumstances of the Great War, a Board of medical men was established, each to have his own patients and none to be in charge of the rest.

Four men were appointed, including Dr Falla who was a notable surgeon, but the 1921 report points out that the problem with this arrangement was that there was not one man directly responsible to the Committee for the medical service.

The report highlights that the administration of the hospital was suffering under this system with no proper stock control nor fire drills. The doctors didn’t appear to communicate with each other and the Superintendent Nurse pointed out that the amount of brandy consumed in the hospital had increased significantly, with patients being refused brandy by one doctor but then asking another and being given a tot.

The report recommended that a Resident Medical Officer was appointed to take charge of the hospital administration in reference to the nursing and care of the sick and that he should be assisted by two medical men, nominated by him and approved by the Committee.

St Helier Police Register

The St Helier Police Register gives details of those arrested in the Parish from 1921 to 1922. The register lists the date, individual arrested, their age, crime, who they were arrested by and witnesses, and the outcome of their case.

Many entries are for relatively minor crimes. On 15 October 1921, Alexander Graham from Stratford was arrested for selling fish less than eight inches long at his store situated at 1, Colomberie in contravention of the Law on Fishing and the Sale of Fish. On same day, Ernest Le Sueur, aged 18, was arrested for driving his motor bike too fast and too dangerously in Stopford Road. Both men were fined £1 for their crimes and Le Sueur had his licence endorsed.

There are a number of incidences of people causing a nuisance, many whilst under the influence of drink and also cases of petty theft, such as Edward Cauvain who was arrested for stealing a horse blanket from the property of Desire Ange in Drury Lane. Edward was released due to a lack of evidence.

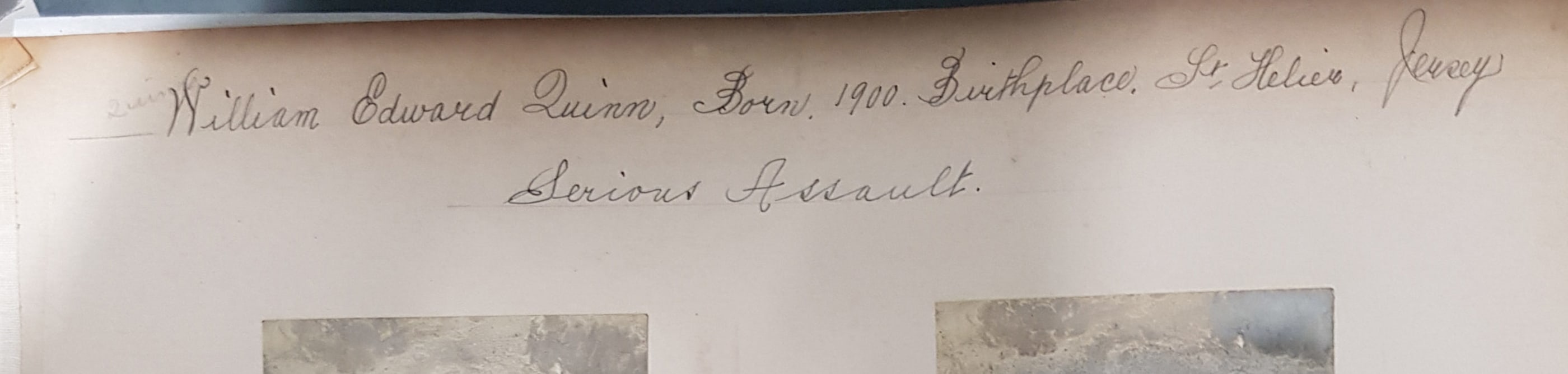

The volume also includes more serious cases of assault, ill-treatment and abandonment of wives and children. One such case is that of William Edward Quinn, who was arrested on 18 April 1922. Quinn was born in St Helier and was 22 years old at the time of his arrest. The register shows that on 17 April at around 9.30pm, Quinn committed a grave assault on Arthur George Gottard and Francois Nicholas by stabbing them on the hands and arms with a knife causing serious injuries. He also threatened to stab a third man, Pierre Marie Guillou.

The Court case shows that Quinn was trying to enter the Gottard’s House in Market Street and when coming out to see what was happening, Mr Gottard was stabbed. Quinn also stabbed Nicholas, who he had been drinking with and threatened Guillou when he tried to take the knife from him. The case went to the Royal Court where Quinn was defended by a young Alexander Coutanche (the future Bailiff of Jersey), who pleaded that Quinn’s naval record was good and that this was his first offence. The Attorney General agreed with a more lenient sentence and ordered that Quinn serve two months with hard labour.

On 15 May, Harry Adone Smith, aged 36 and born in St Helier, was arrested for stealing from his employers, Le Riches in Colomberie Street. The arrest register goes into great detail listing the items that were stolen and taken back to his house, Melrose Villa in Trinity Road. The list includes a packet of cake flour costing 9p, some granulated sugar costing 10p, a box of currants and a box of margarine, which leads one to wonder if he was intending to make a cake!

The Court case shows that Smith had been sending parcels of groceries to his own home for some weeks and making up false orders. He was sentenced to one month of hard labour.

On 25 July, Walter Samuel Wain, from Birmingham, appears in the register. Wain was accused of using gross and disgusting language in the Pomme d’Or Hotel garden, having grossly insulted James Mayall and also having in his possession dice to be used for the purpose of playing Crown and Anchor.

In Court, Wain said that he had no intention of playing Crown and Anchor and that he was sorry for what had happened. He also told the sitting Magistrate that the game of Crown and Anchor had helped win the war, stating: ‘That’s how we fought the Germans’. The Magistrate fined Wain £2 and gave him back his Crown and Anchor dice, saying: ‘Be careful the police don’t see you playing with them’. Wain answered: ‘They might want to have a game’.

In August 1922, Harold Lamerton was arrested and charged with climbing over the railings of the General Hospital at 4am, entering one of the isolation wards with criminal intent and stealing a cup of Bovril.

For this crime he was sentenced to three months hard labour, which seems particularly harsh for the theft of a cup of Bovril. However, Court records show that although the case first came up before the Police Court, it was then sent to the Royal Court as Lamerton was a repeat offender. In the Royal Court, it was revealed that this was his 20th sentence, including previous offences of highway robbery, violence and intemperance. The Public Prosecutor therefore argued for a total of six months hard labour. A division in sentencing between the sitting Jurats led to the Bailiff to give the prisoner the benefit of leniency and opting for the three month sentence.

On November 13, the register shows that John Acourt was arrested for an infraction of the Law on Primary Instruction. Acourt had not been sending his daughter, Violet, to school on a regular basis, as required by law. In Court, Mr J Le Breton, the school attendance officer, gave evidence that Violet had only attended school seven times out of a possible 40 in October and 24 out of 32 in September. Acourt was fined 5 shillings and told to send his daughter to school regularly.

Alien’s Office File

The file begins with a letter from Rudolf Reich, of Vienna, to the Alien’s Office in Jersey. The letter is dated 16 September 1938, six months after German troops had invaded Austria and incorporated the country into the German Reich in what was known as the Anschluss.

The letter shows that Rudolf and his family were Jewish. The family consisted of Rudolf’s wife and daughter, who had already been able to find work in England and Rudolf and his son Erich, who are applying to come to Jersey.

In the letter Rudolph writes: ‘I beg you once more to help my unhappy son and me out of our miserable situation. We are both healthy and willing to do every work. I expect an answer in a short time, which will save us and give us a possibility to live as human beings.’

Following the annexation of Austria and during the spring, summer and autumn of 1938, waves of street violence against Jewish people and their property swept through Vienna and other Austrian cities. Rudolph was clearly looking to escape this regime.

Rudolph’s application was passed to Government House, which sought the opinion of the Defence Committee. The Defence Committee considered the application but recommended that it would be ‘undesirable that the application be granted’.

Rudolph was informed of the Committee’s decision but wrote again to ask the Island’s authorities to reconsider. However, the response was that the decision was final.

Archive evidence shows that Rudolph did manage to leave Austria. He was interned in England as a German Citizen in June 1940 but released a few months later. His release papers show that he was working as a manager of a leather shop in Berkshire.

Erich, Rudolph’s son, also managed to leave Austria. He appears on the England and Wales register for 1939 in Hackney, working as a trainee in a shoe factory. Records on ‘Ancestry’ show that Erich was one of around 10,000 children transported from German through the Kindertransport programme, which ran in 1938 – 1939.

It was the Defence Committee’s job to make decisions in cases such as Rudolph’s. The Committee received annual reports from the Immigration Officer’s in Jersey and in February 1937, they set up a sub-committee to look at the subject of ‘foreigners’ in Jersey. The sub-committee were to meet with the Bailiff and representatives from the Home Office to discuss the matter.

On 16 March, the Defence Committee minutes record that the agreement reached following a meeting between the local authorities and the Home Office was that new draft legislation on ‘foreigners’ would allow the Committee to suggest that the Superintendent of Police should be entrusted with registering aliens.

The new Law on Foreigners was passed in 1937 and gave the Defence Committee the responsibility for appointing Alien’s Officers to carry out the legislation.

In July 1937, the Committee considered the first request under the Law from an individual who wanted to permanently settle in the Island. The application was from Georges Gavrilenko and his nationality is given as ‘White Russian’. The Committee refused permission as they did not see that his application was in the interests of the Island.

From March 1938, the Committee minutes show a number of individuals asking for permission to set up businesses and work in the Island. Some of them, such as Pierre Galitch, a hairdresser from Russia, are permitted and some, such as Tito Fortuna, an Italian ice cream maker, are refused.

In July 1938, the Committee discuss the Conference of Evian at which delegates from 32 countries met to discuss the refugee crisis in which Jewish people sought to flee Nazi persecution. They also discuss the concern, highlighted by the Lieutenant Governor, that recent German legislation has deprived certain subjects of their nationality and excluded them from German territory, meaning that any refugees admitted could not be repatriated in due course and would have to be supported by the public finances.

The Committee agree to await the recommendations of the Conference before making any decisions. At the Conference, 31 countries did not change their policy on refugees and whilst the Committee did not mention the Conference again, we can assume that this impacted on their decisions.

A month later, the Committee considered the case of Leopold Redlich and his wife Helene, who was an Austrian Jew. The couple were already in the Island, working as part of a cabaret act in a number of hotels. The Committee felt that these were special circumstances and allowed Leopold and Helene to continue to be employed until the end of the season.

In September 1938, Rudolf’s request is brought before the Committee alongside four others from individuals of German or Austrian nationality – all five are refused permits to come to Jersey.