A letter donated to Jersey Archive in May 2024 may have finally revealed the truth about an infamous hotel fire that has been subject to speculation and rumour for nearly 80 years

A letter donated to Jersey Archive in May 2024 may have finally revealed the truth about an infamous hotel fire that has been subject to speculation and rumour for nearly 80 years.

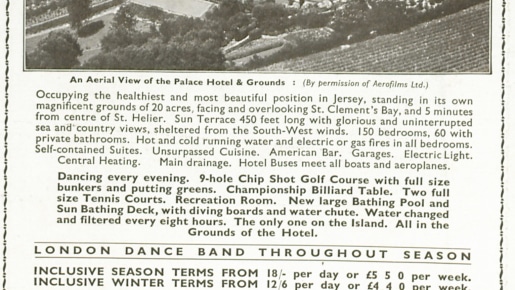

On the morning of 7 March 1945, residents of St Saviour and St Helier were shaken by a massive explosion after a fire at Palace Hotel rapidly got out of control. Having been requisitioned by German forces at the start of the Occupation, at the time it exploded, it is believed that German troops were using the hotel to plan for a raid on Granville.

In an attempt to put out a fire that had initially broken out in a munitions store at the hotel, it is believed that the Germans set off explosives in an attempt to create a firebreak. However, this went disastrously wrong and triggered a series of explosions, leading to its complete destruction. Nine German officers are believed to have died, and dozens of others injured.

While many have theorised that the initial fire was a deliberate act of resistance, no-one has ever claimed responsibility or provided any proof as to how the fire may have started. A letter deposited at Jersey Archive in May 2024 provides some important details that may at long last answer the mystery of how the fire started.

Opened in 1930, just 15 years before it saw its dramatic end, the Palace Hotel was a grand building that once stood in 20 acres of grounds off Bagatelle Road on the former site of a boarding school ran by the sisters of FCJ. Boasting views overlooking St Clement’s Bay, a 1930s advertising brochure notes that the 150-room hotel included among its amenities a nine-hole golf course with full size bunkers and putting greens, two full size tennis courts and a large bathing pool with diving boards and ‘water chute’.

Despite its significance, the fire was never reported upon in the Evening Post in the days that followed, likely due to the fact that the paper was under the censorship of the occupying forces, which allowed them to limit the flow of information to islanders.

Describing the incident in his Occupation diary, Leslie Sinel wrote that houses nearby suffered from damage to windows, doors, ceilings and roofs, with flying debris covering the area. After the war, the hotel’s proprietor wrote to the Channel Islands Rehabilitation Scheme claiming over £50,000 in damages, but the hotel, which was completely destroyed in the explosion, was never rebuilt. Palace Close, built in the 1960s, now stands on the former hotel site.

Image ref D/AP/T/A/116

Full page advertisement for the Palace Hotel in the 1930s

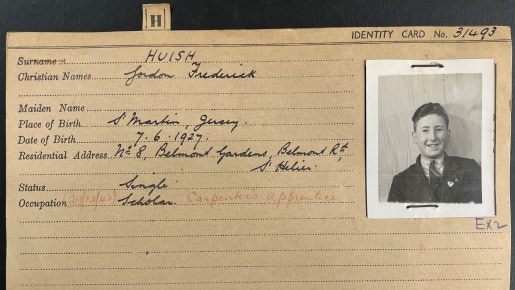

In May 2024, a handwritten letter signed by Gordon Frederick Huish was brought all the way to Jersey Archive from New Zealand by Gordon’s daughter. Titled ‘The Bombing of the Palace Hotel, Jersey’, the letter is dated 7 March 2017, 72 years to the day after the fire. Gordon starts by explaining the reason for writing the letter:

‘As I am approaching my 90th year on June 7 and am the sole survivor who knows the true story of the events of March 7 1945 which led to the destruction of the Palace Hotel, I will describe truthfully exactly how it happened.’

Image ref L/F/820

Gordon Huish's letter detailing his account of the Palace Hotel fire

In the letter, Gordon recalls that on 5 March, Norman Le Brocq – arguably the leading figure of the anti-Nazi resistance movement in Jersey during the Occupation – visited him at his home, which we know from his Occupation registration card was 8, Belmont Gardens. Le Brocq asked him to ‘deliver a parcel for him’, which he said he would, albeit ‘reluctantly’. Le Brocq then told him to go to 3, Hue Street the following day as he wanted him ‘to meet someone’.

A founding member of the Jersey Communist Party and the Jersey Democratic Movement, in 1965, Le Brocq was one of 18 people awarded an inscribed gold watch by the Soviet ambassador in recognition for his help assisting Russian prisoners during the Occupation. Between 1966 and 1987, he spent long periods serving as a Deputy of St Helier in the States Assembly.

Image credit – Jersey Evening Post L/A/75/A2/POR/63/7

Norman Le Brocq in May 1965 ahead of receiving an award from Russia in recognition of the help he gave to Russian prisoners during the Occupation

Gordon describes how when he arrived at 3, Hue Street, Le Brocq was accompanied by a German soldier whom Le Brocq introduced to him as ‘Willi’ saying, “It’s alright. He’s a friend.” When asked whether he would recognise Willi again, Gordon said he would.

He writes that he was then told to go to Paragon Garage on Halkett Place ‘the following day at 9.30 a.m. to pick up the parcel and to deliver it to Willi who would be waiting at the entrance to the Palace Hotel’. He was told the delivery ‘had to be made before 10.00 a.m.’ and that he was asked if he had any gloves. When he responded that he only had mittens, he was told ‘to wear them’.

Gordon describes that he went to the garage, as instructed, where he was met by Le Brocq. He was handed ‘a parcel covered in brown paper and tied up with strong string through a hatch in the wall’ by two men who ‘appeared to not want to be recognised’, but who he positively identifies as Leonard Perkins and Leslie Huelin. Both were close compatriots of Le Brocq and fellow members of the Jersey Communist Party and resistance movement.

Image credit – Jersey Evening Post L/A/75/A2/POR/26/10

Portrait of Leonard Perkins taken in the weeks leading up to his unsuccessful bid to be elected as a Deputy of St Helier in December 1951

Gordon states that he was given specific instructions ‘not to speak to Willi, to just hand him the parcel and keep walking’. He recalls that when he arrived at the Palace Hotel on 7 March, ‘Willi was waiting at the entrance’ and that when he handed over the parcel ‘[Willi] smiled and I kept walking up Mont Millais’. Describing the parcel, Gordon notes ‘by its weight and feeling the terminals through the thick brown paper, I thought was a car battery’.

After delivering the parcel, Gordon ‘heard a very loud explosion’ and ‘shortly after a lot of German field ambulances came tearing down the road’. At this point, he ‘began to feel uneasy’ and his ‘instinct’ told him ‘to get out of the area as quickly as [he] could’. He continued walking towards St Saviour’s Church, before walking down St Saviour’s Road back to St Helier.

In the letter, Gordon clarifies: ‘When I picked up and delivered the parcel, I did not know the purpose for which it was intended’ and that while he heard the first explosion, he knew ‘nothing of the subsequent explosions and the fire’.

Image ref – L/C/14/B/9/1/2

Aerial image of the hotel

Gordon goes on to explain how after the war, he learnt that ‘Willi’s real name was Obergefreiter (Corporal) Paul Mulbach’. Paul Mülbach, whose father had died after being sent to a concentration camp by the Nazis, was a German soldier based in Jersey during the Occupation who became an important figure in the resistance movement.

Mülbach has a recorded association with Le Brocq and his communist comrades, who helped produce leaflets intended to help Mülbach incite a mutiny against the German garrison. According to Gordon, Mülbach deserted the army after the explosion ‘and spent the rest of the war hiding at 3 Hue Street’.

Image ref – L/F/62/A/4

Paul Mülbach in officer uniform during the Second World War

While Le Brocq and Mülbach have often been rumoured to have been involved in the fire, Gordon Huish has never been linked in any way to the destruction of the Palace Hotel. Other records held at Jersey Archive show that Gordon, who was just 17 at the time he delivered the parcel to the Palace Hotel, worked as an apprentice carpenter during the war, and provide more information about his early years, upbringing and education.

Gordon moved to New Zealand in the early 1950s where he settled down and raised a family. He died in Auckland, aged 95, on 23 March 2023, six years after writing the letter. According to his daughter, it was her father’s express wish that his letter was brought to Jersey so that his account of the events of March 1945 could finally be told.

Gordon’s letter detailing his unique account of the events that led to the destruction of the Palace Hotel provides a fascinating new insight into this aspect of the Island’s story, which is told through the millions of archives and objects looked after by Jersey Heritage.

Image ref – D/S/A/4/A6181

Occupation registration card of Gordon Frederick Huish