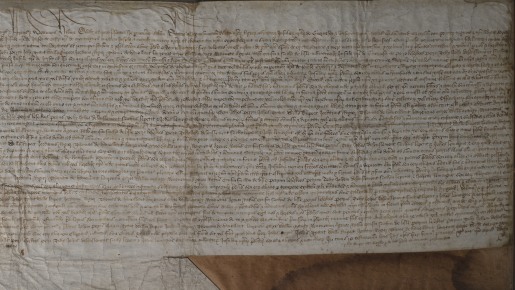

Royal Charters were issued by the Monarch as a solemn grant of land, privileges, exemptions or immunity. Jersey’s Royal Charters confirm and enhance the rights, liberties and privileges of the Island.

Edward IV’s charter was issued to the Island during the War of the Roses and following the French Occupation of Jersey from 1461 – 1468.

In the spring of 1461 Mont Orgueil Castle was raided by a French Force under Jean Carbonnel. The French remained in charge of the Island until, in 1468, Richard Harliston, a Yorkist Vice-Admiral dedicated to the cause of Edward IV secretly landed on the Island and met with Philippe de Carteret, Seigneur of St Ouen. de Carteret was a leading figure of resistance against the French Occupation.

Harliston and de Carteret mustered local troops and laid siege to the French forces at Mont Orgueil on 17 May 1468. The siege lasted for just over 6 months until the Castle finally had to surrender and the Island was reclaimed for the England Crown.

On 28 January 1469 Edward IV confirmed all Jersey’s ancient franchise and gave the people of Jersey freedom from charges made in cities in England:

‘bearing in mind with what constancy and courage the community has proved loyal to us and our forefathers and how many perils and losses they have borne in reducing our Castle of Mont Orgill’

This charter, issued later that year, indicates that Edward, despite praising the ‘great fealty’ of the inhabitants of Jersey, expects compensation from the Channel Islands of the sum of £2,833 6 shillings 8 pence for the

‘re-taking of our said Island of Jersey and Castle of Mont Orgueil on the same Island’

This is a tremendous sum of money given that Jersey was recovering from the effects of occupation – the equivalent worth today is reckoned at £1.4 million. Edward does, however, offer trade incentives to Islanders which he hopes will help them pay the compensation.

Edward shows his concern that this sum will lead to the ‘manifest impoverishment’ of the people of the Islands unless they are ‘by us the same be aided’. He talks of the ‘great fealty’ that the Island have shown the Crown and to assist with the payment of the recompense by the Islands he uses this document to establish a grant to a number of individuals including John Desouslemont, Nicholas Lepetit and John Lemoigne.

The grant gives these people or their representatives the right to trade their own goods and also those of other Islanders as follows;

‘so much, so many and so great trades and buying’s whatsoever of our Staple of Calais, in the least degree pertaining, within our Kingdom of England, (to) themself, and to provide for and the same thus gaining and provided for, in whatsoever ship…….from our homage at one time or diverse times in our ports of Poole, Exeter and Dartmouth….’

Although a community of English merchants concerned with the export trade existed before this time, the Company of the Staple can be confidently traced back to 1359, when the first royal grant was issued giving the merchants unequivocal control of the export trade in staple commodities. In 1363 the “Community of the Merchant of the Staples” moved to Calais from Bruges and soon became known as the Mayor and Company of the Merchants of the Staple of England.

In order to ship wool to Calais a merchant had to be a member of the Company and to obey its ordinances. Admission could be gained through a three to four year apprenticeship or by purchase and by the end of the fifteenth century, nearly 400 men were members. The Company enjoyed great wealth and controlled the English wool trade until the loss of Calais in 1558, by which time changes in the English textile industry were also undermining their trade.

If the Islanders find that they have £150 each year over, after paying customary dues and costs, this money is to be paid towards the recompense.

This type of grant seems to be in keeping with Edward’s own trading ambitions. Edward built closer relations with the merchant community and encouraged commercial treaties. He successfully traded wool on his own account to restore his family’s fortunes and thus freeing him from dependence on subsidies from Parliament. Through this document he appears to be encouraging the people of Jersey to do the same.

Edward IV Charter